Thank you for requesting that Micky Metts speak at your event. She will respond as soon as she can and let you know if she is available, or if she has any questions.

Agaric Team

Learning online has become a necessity for schools and independent teachers and tutors. Agaric can provide a Learning Management System (LMS) to support your teaching skills and knowledge integrated with video chat and whiteboard features. Every component of our platform is 100% Free/Libre Software because we believe in protecting the privacy of our students!

Let us know what you need and we can set up a time to discuss your unique situation.

Here you will find the details of our online learning tools.

Learning Management System

The Canvas learning management platform allows you or your organization to build the digital learning environment that meets the unique challenges faced by your institution. Canvas LMS allows teachers to create courses and grade students. Developed in 2011, Canvas was designed to better engage people in teaching and learning processes.

Canvas is integrated with video chat software called BigBlueButton and it works to seamlessly allow teachers and students, if given the permission, to create live conferences with many features for moderation and engagement for all participants. Both Canvas and BigBlueButton are free open source software because our mission includes privacy for all and the ability to freely modify the software to suit your needs.

Canvas LMS Features:

- Practice Tests, or Quizzes – These are assignments, groups of questions, that can be used to challenge student understanding and assess comprehension. Question types include multiple choice, true/false, fill in the blanks, multiple answers, matching, numerical answers, formulas, and long text (freeform/essay).

- Question Banks – Group quiz questions in question banks to create grade, topic, institutional, or departmental question repositories.

- Outcomes – Outcomes (also called standards or competencies) describe what a learner should be able to do and are used to measure knowledge and ability.

- Mastery Paths – This tool allows course content to automatically be released to a learner based on performance, providing differentiation to students.

- Canvas Data – Canvas Data allows instructors to parse Canvas-generated data quickly.

- Canvas Commons – Canvas Commons is a repository that lets users easily share content.

- Integrated Media Recorder – This tool allows users to record audio and video messages for the digital classroom.

- Web conferencing – Set a meeting time for the whole class or one-on-one synchronous online discussions.

- Mastery Gradebook – Helps instructors assess the Outcomes being used in Canvas courses and measure student learning for accreditation or standards-based grading.

- Canvas Parent – Canvas Parent allows parents to engage with their children’s education by reviewing upcoming or past assignments, checking grades and receiving course announcements.

- Canvas Polls – An app (available on iOS and Android) that gauges students’ comprehension of material without “clicker” devices.

Videochat and whiteboard

The BigBlueButton video and whiteboard software is integrated into the Canvas dashboard and allows teachers and students to meet in a live learning environment that brings interactivity to the forefront. BigBlueButton is a free open-source web conferencing system designed for online classes, workshops and lectures. BigBlueButton allows teachers to create breakout rooms for different levels of learning.

Big Blue Button Features:

- Accounts and Profile

- Sign up / Login

- Profile

- Conference Rooms

- Create New Conference Rooms

- Breakout Rooms

- Conference Settings

- Rename Conference

- Manage Access to Conferences

- Record Conference

- View Recordings

- Manage Recordings

- Modify Recordings

- Sort and Search Recordings

Drupal content management platform

You can provide a simple website for your school by building on the Drupal platform, the Canvas learning management platform automatically has access to a large number of features that are built into Drupal. We describe some important ones here, though there are many more.

Content editing with Drupal

- Build your website with basic pages, landing pages, news postings, and more.

- Create instructional guides and reference links to relevant information.

- Engage the students in making additions to the site and maintaining the content.

- Optionally, use a content moderation workflow in which a content editor can approve draft content.

- Restore deleted content (retrieve from trash), so student exercises involving creating content on the site are not lost.

- Administrators can set permissions on any content and allow access in a granular way.

What will you provide for your students?

Kathleen was an Agaric principal for the year of 2009, working especially on the Science Collaboration Framework project of Harvard University and Massachusetts General Hospital, including its use in Parkinson's disease research in partnership with the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson's Research.

A great communicator and team organizer, Kathleen is a prodigious learner and powers through any technical challenges that needs to be overcome. With a background in architecture, visual arts, and the history of art and architecture, her embrace of web technology polymath.

Six years before Drupal 8's configuration management, Kathleen developed the database scripts project to separate configuration settings in the database from content, and allow configuration from a development environment to be brought to production. These scripts, operating as they did primarily by sheer force of will, always worked best with Kathleen at the helm.

She loves web development and photography, both fusions of art and technology. Presently unable to work for sustained periods on a computer, she is plotting an epic science fiction novel and trying to increase the ways people with disabilities can be economically active.

There are plenty of ways—all right, too many ways—to create links when using modern Drupal (Drupal 8 and above, so including so far Drupal 9, Drupal 10, and Drupal 11). We will share some of those ways in this regularly-updated post. (Latest update: 2025 September 22)

The easiest way to create internal links is using Link::createFromRoute

And it is used like this:

use Drupal\Core\Link;

$link = Link::createFromRoute(t('This is a link'), 'entity.node.canonical', ['node' => 1]);

Using the Url object gives you more flexibility to create links, for instance, we can do the same as Link::createFromRoute method using the Url object like this:

use Drupal\Core\Link;

use Drupal\Core\Url;

$link = Link::fromTextAndUrl(t('This is a link'), Url::fromRoute('entity.node.canonical', ['node' => 1]));

And actually Link::fromTextAndUrl is what Drupal recommends instead of using the deprecated l() method. Note that as before, the text portion of the link should already be translated, so wrap it in t() or, for object-oriented code, $this->t(). Passing the Url object to the link object gives you great flexibility to create links, here are some examples:

Internal links which have no routes:

$link = Link::fromTextAndUrl(t('This is a link'), Url::fromUri('base:robots.txt'));

External links:

$link = Link::fromTextAndUrl(t('This is a link'), Url::fromUri('http://www.google.com'));

links with only the fragment (without url) :

$link = Link::fromTextAndUrl(t('This is a link'), Url::fromUri('internal:#fragment'));

Using the data provided by a user:

$link = Link::fromTextAndUrl(t('This is a link'), Url::fromUserInput('/node/1');

The param passed to fromUserInput must start with /,#,? or it will throw an exception.

Linking entities.

$link = Link::fromTextAndUrl(t('This is a link'), Url::fromUri('entity:node/1'));

Entities are a special case, and there are more ways to link them:

$node = Node::load(1);

$link = $node->toLink();

$link->setText(t('This is a link'));

And even using the route:

$link = Link::fromTextAndUrl(t('This is a link'), Url::fromRoute('entity.node.canonical', ['node' => 1]));

Drupal usually expects a render array if you are going to print the link, so the Link object has a method for that:

$link->toRenderable();

which will return an array.

To get the absolute URL (that is, the one that likely starts with "https" and your domain name) for a piece of content (node) or other entity, you can do:

$absolute_url = $node->toUrl('canonical', ['absolute' => TRUE]);Linking files.

Files are entities also in Drupal but a special kind. You usually do not want to link to the entity but directly to the uploaded file. To do that, do not use $file->getFileUri() but rather instead use createFileUrl() which will directly give you a complete string version of the URI:

$url =$file->createFileUrl();

This URL can then be used in making a link with regular HTML or the External links approach covered above.

Credit to godotislate in Drupal Slack support channel for this tip.

Final tips:

Searching a route using Drupal Console

The easiest way to find the route of a specific path is using Drupal Console, with the following command.

$ drupal router:debug | grep -i "\/node"

That will return something like:

entity.node.canonical /node/{node}

entity.node.delete_form /node/{node}/delete

entity.node.edit_form /node/{node}/edit

entity.node.preview /node/preview/{node_preview}/{view_mode_id}

entity.node.revision /node/{node}/revisions/{node_revision}/view

entity.node.version_history /node/{node}/revisions

node.add /node/add/{node_type}

node.add_page /node/add

node.multiple_delete_confirm /admin/content/node/delete

node.revision_delete_confirm /node/{node}/revisions/{node_revision}/delete

node.revision_revert_confirm /node/{node}/revisions/{node_revision}/revert

node.revision_revert_translation_confirm /node/{node}/revisions/{node_revision}/revert/{langcode}

search.help_node_search /search/node/help

search.view_node_search /search/node

view.frontpage.page_1 /node

Listing all the possible routes with that word, we can choose one and do:

drupal router:debug entity.node.canonical

And that will display more information about a specific route:

Route entity.node.canonical

Path /node/{node}

Defaults

_controller \Drupal\node\Controller\NodeViewController::view

_title_callback \Drupal\node\Controller\NodeViewController::title

Requirements

node \d+

_entity_access node.view

_method GET|POST

Options

compiler_class \Drupal\Core\Routing\RouteCompiler

parameters node:

type: 'entity:node'

converter: paramconverter.entity

_route_filters method_filter

content_type_header_matcher

_route_enhancers route_enhancer.param_conversion

_access_checks access_check.entity

So in this way we can search the route without the needing to search in all the *.routing.yml files and in this example the route is entity.node.canonical and the param expected is node.

Print links directly within a twig template

It is also possible to print links directly on the twig template with the following syntax:

<a href="{{url('entity.node.canonical', {'node': node.id( ) }}"> {{ 'This is a link'|t }} </a>

Add links inside a t() method.

If you want to add a link inside the t() you can do what Drupal suggests on Dynamic or static links and HTML in translatable strings:

use Drupal\Core\Url;

$url = Url::fromRoute('entity.node.canonical', ['node' => 1]);

$this->t('You can click this <a href=":link">Link</a>', [':link' => $url->toString()]);

Or, from a node object:

$markup = $this->t('You found this node: <a href=":url">@title</a>', [

':url' => $node->toUrl('canonical'),

'@title' => $node->label(),

]);

Articles and talks that engage in broad themes from Micky's talk

- There is no halfway in the fight against injustice

- GNU Philosophy

- Love and Money by Audrey Eschright

- Free Software and the shifting landscape of online cooperation by Benjamin Mako Hill

- How Drupal as a Service can save us all by Benjamin Melançon

- Platform Cooperativism by Trebor Scholz

Whole books:

- Collective Courage: A History of African American Cooperative Economic Thought and Practice by Jessica Gordon Nembhard

- Ours to Hack and to Own

- Jackson Rising: The Struggle for Economic Democracy and Black Self-Determination in Jackson, Mississippi

- Twitter and Teargas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest by Zeynep Tufekci

- The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power by Shoshana Zuboff

We are Agaric Technology Collective, a worker-owned cooperative. We build websites and online tools that respect your freedom. We provide training and consultation to meet your goals.

We build websites that matter

From digital collaboration spaces for health and science communities to publishing platforms to opportunity finders for city residents, we love to do the hard work that supports people doing the harder work of making the world better. Some of our best work is done when we just ensure that the world can see the great work done by an organization.

We go deep

From our founding in 2006, our approach has been to deeply engage with the needs of our clients and collaborate with free/libre open source software communities to craft solid, sustainable solutions.

We raise you up

At every opportunity, we provide training and build our clients' capacity to take more control over their web presence. By building on software that belongs to everyone and has large communities, we ensure organizations we work with have options and room to grow. By eagerly and expertly teaching whatever people are willing to learn, from basic organizational security to migrating data to software development to content strategy, we stay true to our purpose of giving people and organizations more power to do good.

Please learn more about our skills and services and contact Agaric!

Web platforms we develop include the Find It program locator to help people find opportunities in their cities and online science and health communities.

Agaric is a worker-owned cooperative and the online tools we build respect your freedom and increase your power to do good. Our trainings range from one-on-one capacity building to day-long group workshops such as our sought-after Migration to Drupal trainings.

Ask Agaric to help you gain power over your online technology today.

Drupal 9 Component Plugin ContextException "not a valid context"

after CTools, Symfony update

2017 was an amazing year for me. I met so many people, attended lots of events, presented a good amount of sessions and trainings, and traveled like never before. I got to interact with the Drupal community in many ways. And I learned so much, both technical and life lessons. Let me share a summary of my year.

To make the text compact I will use some abbreviations in the text. DC for DrupalCamp and GTD for Global Training Days. Meetups refers to local user groups meetings.

Events per month

- January: No event.

- February: Boston meetup, New Jersey, Florida DC, and Northern Lights DC.

- March: DC London, GTD Managua, NERD Summit, DevDays Seville, and MidCamp.

- April: Boston meetup and DrupalCon Baltimore.

- May: Managua meetup and WordCamp Managua.

- June: Texas DC, Boston meetup, GTD Managua, ECWD, and Twin Cities DC.

- July: No event.

- August: DC Costa Rica and Managua meetup.

- September: Synergy Camp, DC Antwerp, GTD Frankfurt, GTD Managua, and DrupalCon Vienna.

- October: Madrid meetup, London meetup, and BADCamp.

- November: Managua meetup and Lakes and Volcanoes DC.

- December: GTD Leon, GTD Managua, and Managua meetup.

This translates to:

- 18 conferences

- 9 meetups

- 12 DrupalCamps

- 2 DrupalCons

- 1 Drupal DevDays

- 12 sessions presented

- 4 trainings presented

- 6 GTD workshop presented

Highlights this year

- Made it into MAINTAINERS.txt as part of the Core mentoring coordinators team.

- Served as part of the Global Training Days community working group.

- Presented a session at DrupalCon.

- Was invited to be a DrupalCon track chair.

- People I mentored at DrupalCon got their patches committed. Thanks to Jess (xjm), Ted Bowman, and other contributors for following up.

Thank you all

Thanks to my colleagues at Agaric for their support during my Drupal tour.

Thanks to all the event organizers who gave me the opportunity to speak at their events. And thanks to all the people who gave feedback of my sessions, trainings, and workshops.

Thanks to Baddý Breidert, Hilmar Hallbjörnsson, and all the team who organized Northern Lights DrupalCamp. They went above and beyond to pull out an event against unfavorable conditions. The night before the sessions fell a record breaking amount of snow. The organizers went to pick people up from around Reykjavik and accommodated the schedule nicely. I was trapped in a bus stops, with snow above my knees, when Hilmar and Christoph Breidert picked me up saved me and took me to the venue. On top of everything, the organizers took everyone on free tours around beautiful Iceland. It was amazing!

Thanks to all the people and organizations who set up different events where I could present during my European tour. Cristina Chumillas (Barcelona), Baddý and Christoph of 1xINTERNET (Frankfurt), Valery Lourie and the SynergyCamp team (Sofia), Sven Decabooter and the DC Antwerp team (Antwerp), Ignacio Sánchez (Madrid), and Chandeep Khosa and Gabriele (gambry) (London).

Thanks to those who hosted me during my European tour. Baddý and Christoph of 1xINTERNET in Frankfurt, my colleague Stefan Freudenberg in Hamburg, and Rodrigo Aguilera in Barcelona. They opened the doors to their homes and their families during my stay. I will always be grateful.

Thanks to Anna Mykhailova for co-presenting a training with me at BADCamp.

Thanks to the awesome organizing team of Lakes and Volcanoes DC. In particular to Lucas Hedding who has helped the Nicaraguan Drupal community in countless ways.

Thanks to the Boston Drupal user group for making me feel at home every time I visit.

Thanks to ALL the people I talked to during the 2017 Drupal tour. The Drupal community is super friendly and welcoming. It is so great to be part of it.

Trivia

Zsófi Major sent a t-shirt to Christian López. In its way from DC London to Drupal DevDays Seville, the t-shirt stopped by 9 airports.

V Spagnolo sent a present to Lucas Hedding. In its way from DrupalCon Vienna to Nicaragua, the parcel stopped by 10 airports.

The GTD in Frankfurt was super interesting. I installed Drupal in German. Not knowing the language, I had no idea how to pronounce the text on the screen. The audience was very kind in helping me. By the end of the workshop I was pronouncing some words almost right. ;)

What's next for 2018?

As my fellow drupaler Eduardo (enzo) García says in his end of year recap, travelling takes a lot of energy. I have plans to attend some events in 2018, but not as much as I did in 2017. While staying at home, I will be able to accomplish things that would be difficult otherwise.

I will kickstart my Drupal learning project: understanddrupal.com My goal is to teach Drupal in multiple languages and multiple formats. To start I will produce content in English, Spanish, and French in text and video formats.

I will learn new languages. On the human side, I will start with French and I might give German a try. On the computer side, I will start with JavaScript and then move to Python. At Agaric we serve clients in multiple countries and with different application stacks. Learning new human and computer languages will help me serve better the clients and projects I participate in.

I want to learn new things. Software testing in general and creating applications in React are my first targets. Expect blog posts about my learnings next year.

I want to participate more actively in the free software communities in my country. Drupal, WordPress, JavaScript, and others. I would like to learn from them and share what I have learned in my travels.

Thanks for a fantastic 2017! See you in 2018! :D

In the previous article, we began talking about debugging Drupal migrations. We gave some recommendations of things to do before diving deep into debugging. We also introduced the log process plugin. Today, we are going to show how to use the Migrate Devel module and the debug process plugin. Then we will give some guidelines on using a real debugger like XDebug. Next, we will share tips so you get used to migration errors. Finally, we are going to briefly talk about the migrate:fields-source Drush command. Let’s get started.

The migrate_devel module

The Migrate Devel module is very helpful for debugging migrations. It allows you to visualize the data as it is received from the source, the result of field transformation in the process pipeline, and values that are stored in the destination. It works by adding extra options to Drush commands. When these options are used, you will see more output in the terminal with details on how rows are being processed.

As of this writing, you will need to apply a patch to use this module. Migrate Devel was originally written for Drush 8 which is still supported, but no longer recommended. Instead, you should use at least version 9 of Drush. Between 8 and 9 there were major changes in Drush internals. Commands need to be updated to work with the new version. Unfortunately, the Migrate Devel module is not fully compatible with Drush 9 yet. Most of the benefits listed in the project page have not been ported. For instance, automatically reverting the migrations and applying the changes to the migration files is not yet available. The partial support is still useful and to get it you need to apply the patch from this issue. If you are using the Drush commands provided by Migrate Plus, you will also want to apply this patch. If you are using the Drupal composer template, you can add this to your composer.json to apply both patches:

"extra": {

"patches": {

"drupal/migrate_devel": {

"drush 9 support": "https://www.drupal.org/files/issues/2018-10-08/migrate_devel-drush9-2938677-6.patch"

},

"drupal/migrate_tools": {

"--limit option": "https://www.drupal.org/files/issues/2019-08-19/3024399-55.patch"

}

}

}With the patches applied and the modules installed, you will get two new command line options for the migrate:import command: --migrate-debug and --migrate-debug-pre. The major difference between them is that the latter runs before the destination is saved. Therefore, --migrate-debug-pre does not provide debug information of the destination.

Using any of the flags will produce a lot of debug information for each row being processed. Many times, analyzing a subset of the records is enough to stop potential issues. The patch to Migrate Tools will allow you to use the --limit and --idlist options with the migrate:import command to limit the number of elements to process.

To demonstrate the output generated by the module, let’s use the image migration from the CSV source example. You can get the code at https://github.com/dinarcon/ud_migrations. The following snippets how to execute the import command with the extra debugging options and the resulting output:

# Import only one element.

$ drush migrate:import udm_csv_source_image --migrate-debug --limit=1

# Use the row's unique identifier to limit which element to import.

$ drush migrate:import udm_csv_source_image --migrate-debug --idlist="P01"

$ drush migrate:import udm_csv_source_image --migrate-debug --limit=1

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ $Source │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

array (10) [

'photo_id' => string (3) "P01"

'photo_url' => string (74) "https://agaric.coop/sites/default/files/pictures/picture-15-1421176712.jpg"

'path' => string (76) "modules/custom/ud_migrations/ud_migrations_csv_source/sources/udm_photos.csv"

'ids' => array (1) [

string (8) "photo_id"

]

'header_offset' => NULL

'fields' => array (2) [

array (2) [

'name' => string (8) "photo_id"

'label' => string (8) "Photo ID"

]

array (2) [

'name' => string (9) "photo_url"

'label' => string (9) "Photo URL"

]

]

'delimiter' => string (1) ","

'enclosure' => string (1) """

'escape' => string (1) "\"

'plugin' => string (3) "csv"

]

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ $Destination │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

array (4) [

'psf_destination_filename' => string (25) "picture-15-1421176712.jpg"

'psf_destination_full_path' => string (25) "picture-15-1421176712.jpg"

'psf_source_image_path' => string (74) "https://agaric.coop/sites/default/files/pictures/picture-15-1421176712.jpg"

'uri' => string (29) "./picture-15-1421176712_6.jpg"

]

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ $DestinationIDValues │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

array (1) [

string (1) "3"

]

════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════

Called from +56 /var/www/drupalvm/drupal/web/modules/contrib/migrate_devel/src/EventSubscriber/MigrationEventSubscriber.php

[notice] Processed 1 item (1 created, 0 updated, 0 failed, 0 ignored) - done with 'udm_csv_source_image'In the terminal, you can see the data as it is passed along in the Migrate API. In the $Source, you can see how the source plugin was configured and the different columns for the row being processed. In the $Destination, you can see all the fields that were mapped in the process section and their values after executing all the process plugin transformation. In $DestinationIDValues, you can see the unique identifier of the destination entity that was created. This migration created an image so the destination array has only one element: the file ID (fid). For paragraphs, which are revisioned entities, you will get two values: the id and the revision_id. The following snippet shows the $Destination and $DestinationIDValues sections for the paragraph migration in the same example module:

$ drush migrate:import udm_csv_source_paragraph --migrate-debug --limit=1

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ $Source │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Omitted.

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ $Destination │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

array (3) [

'field_ud_book_paragraph_title' => string (32) "The definitive guide to Drupal 7"

'field_ud_book_paragraph_author' => string UTF-8 (24) "Benjamin Melançon et al."

'type' => string (17) "ud_book_paragraph"

]

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ $DestinationIDValues │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

array (2) [

'id' => string (1) "3"

'revision_id' => string (1) "7"

]

════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════

Called from +56 /var/www/drupalvm/drupal/web/modules/contrib/migrate_devel/src/EventSubscriber/MigrationEventSubscriber.php

[notice] Processed 1 item (1 created, 0 updated, 0 failed, 0 ignored) - done with 'udm_csv_source_paragraph'

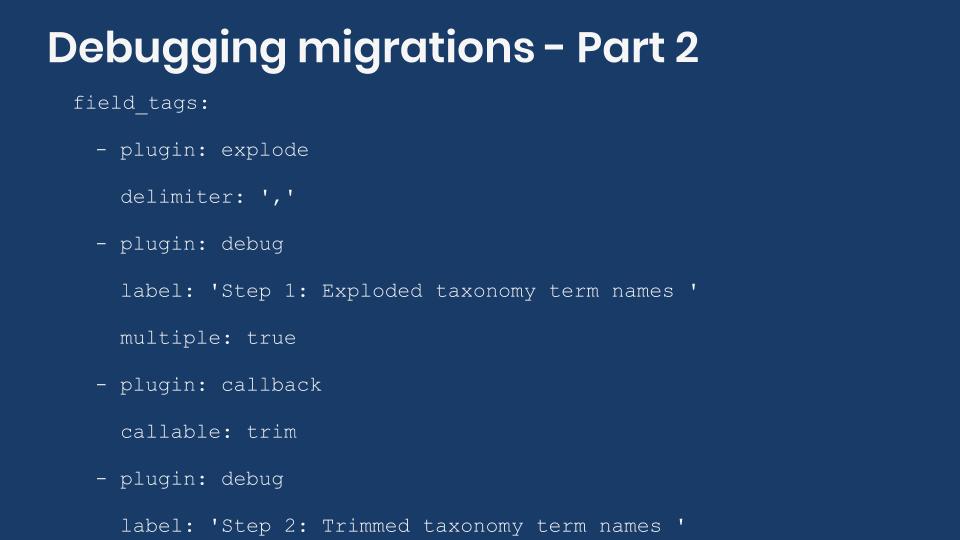

The debug process plugin

The Migrate Devel module also provides a new process plugin called debug. The plugin works by printing the value it receives to the terminal. As Benji Fisher explains in this issue, the debug plugin offers the following advantages over the log plugin provided by the core Migrate API:

- The use of

print_r()handles both arrays and scalar values gracefully. - It is easy to differentiate debugging code that should be removed from logging plugin configuration that should stay.

- It saves time as there is no need to run the

migrate:messagescommand to read the logged values.

In short, you can use the debug plugin in place of log. There is a particular case where using debug is really useful. If used in between of a process plugin chain, you can see how elements are being transformed in each step. The following snippet shows an example of this setup and the output it produces:

field_tags:

- plugin: skip_on_empty

source: src_fruit_list

method: process

message: 'No fruit_list listed.'

- plugin: debug

label: 'Step 1: Value received from the source plugin: '

- plugin: explode

delimiter: ','

- plugin: debug

label: 'Step 2: Exploded taxonomy term names '

multiple: true

- plugin: callback

callable: trim

- plugin: debug

label: 'Step 3: Trimmed taxonomy term names '

- plugin: entity_generate

entity_type: taxonomy_term

value_key: name

bundle_key: vid

bundle: tags

- plugin: debug

label: 'Step 4: Generated taxonomy term IDs '

$ drush migrate:import udm_config_entity_lookup_entity_generate_node --limit=1

Step 1: Value received from the source plugin: Apple, Pear, Banana

Step 2: Exploded taxonomy term names Array

(

[0] => Apple

[1] => Pear

[2] => Banana

)

Step 3: Trimmed taxonomy term names Array

(

[0] => Apple

[1] => Pear

[2] => Banana

)

Step 4: Generated taxonomy term IDs Array

(

[0] => 2

[1] => 3

[2] => 7

)

[notice] Processed 1 item (1 created, 0 updated, 0 failed, 0 ignored) - done with 'udm_config_entity_lookup_entity_generate_node'The process pipeline is part of the node migration from the entity_generate plugin example. In the code snippet, a debug step is added after each plugin in the chain. That way, you can verify that the transformations are happening as expected. In the last step you get an array of the taxonomy term IDs (tid) that will be associated with the field_tags field. Note that this plugin accepts two optional parameters:

labelis a string to print before the debug output. It can be used to give context to what is being printed.multipleis a boolean that when set totruesignals the next plugin in the pipeline to process each element of an array individually. The functionality is similar to themultiple_valuesplugin provided by Migrate Plus.

Using the right tool for the job: a debugger

Many migration issues can be solved by following the recommendations from the previous article and the tools provided by Migrate Devel. But there are problems so complex that you need a full-blown debugger. The many layers of abstraction in Drupal, and the fact that multiple modules might be involved in a single migration, makes the use of debuggers very appealing. With them, you can step through each line of code across multiple files and see how each variable changes over time.

In the next article, we will explain how to configure XDebug to work with PHPStorm and DrupalVM. For now, let’s consider where are good places to add breakpoints. In this article, Lucas Hedding recommends adding them in:

- The

importmethod of the MigrateExecutable class. - The

processRowmethod of the MigrateExecutable class. - The process plugin if you know which one might be causing an issue. The

transformmethod is a good place to set the breakpoint.

The use of a debugger is no guarantee that you will find the solution to your issue. It will depend on many factors, including your familiarity with the system and how deep lies the problem. Previous debugging experience, even if not directly related to migrations, will help a lot. Do not get discouraged if it takes you too much time to discover what is causing the problem or if you cannot find it at all. Each time you will get a better understanding of the system.

Adam Globus-Hoenich, a migrate maintainer, once told me that the Migrate API "is impossible to understand for people that are not migrate maintainers." That was after spending about an hour together trying to debug an issue and failing to make it work. I mention this not with the intention to discourage you. But to illustrate that no single person knows everything about the Migrate API and even their maintainers can have a hard time debugging issues. Personally, I have spent countless hours in the debugger tracking how the data flows from the source to the destination entities. It is mind-blowing, and I barely understand what is going on. The community has come together to produce a fantastic piece of software. Anyone who uses the Migrate API is standing on the shoulders of giants.

If it is not broken, break it on purpose

One of the best ways to reduce the time you spend debugging an issue is having experience with a similar problem. A great way to learn is by finding a working example and breaking it on purpose. This will let you get familiar with the requirements and assumptions made by the system and the errors it produces.

Throughout the series, we have created many examples. We have made our best effort to explain how each example work. But we were not able to document every detail in the articles. In part to keep them within a reasonable length. But also, because we do not fully comprehend the system. In any case, we highly encourage you to take the examples and break them in every imaginable way. Making one change at a time, see how the migration behaves and what errors are produced. These are some things to try:

- Do not leave a space after a colon (:) when setting a configuration option. Example:

id:this_is_going_to_be_fun. - Change the indentation of plugin definitions.

- Try to use a plugin provided by a contributed module that is not enabled.

- Do not set a required plugin configuration option.

- Leave out a full section like source, process, or destination.

- Mix the upper and lowercase letters in configuration options, variables, pseudofields, etc.

- Try to convert a migration managed as code to configuration; and vice versa.

The migrate:fields-source Drush command

Before wrapping up the discussion on debugging migrations, let’s quickly cover the migrate:fields-source Drush command. It lists all the fields available in the source that can be used later in the process section. Many source plugins require that you manually set the list of fields to fetch from the source. Because of this, the information provided by this command is redundant most of the time. However, it is particularly useful with CSV source migrations. The CSV plugin automatically includes all the columns in the file. Executing this command will let you know which columns are available. For example, running drush migrate:fields-source udm_csv_source_node produces the following output in the terminal:

$ drush migrate:fields-source udm_csv_source_node

-------------- -------------

Machine Name Description

-------------- -------------

unique_id unique_id

name name

photo_file photo_file

book_ref book_ref

-------------- -------------The migration is part of the CSV source example. By running the command you can see that the file contains four columns. The values under "Machine Name" are the ones you are going to use for field mappings in the process section. The Drush command has a --format option that lets you change the format of the output. Execute drush migrate:fields-source --help to get a list of valid formats.

What did you learn in today’s blog post? Have you ever used the migrate devel module for debugging purposes? What is your strategy when using a debugger like XDebug? Any debugging tips that have been useful to you? Share your answers in the comments. Also, I would be grateful if you shared this blog post with others.

This blog post series, cross-posted at UnderstandDrupal.com as well as here on Agaric.coop, is made possible thanks to these generous sponsors. Contact Understand Drupal if your organization would like to support this documentation project, whether it is the migration series or other topics.

El Enfoque

Experiencia de autor: simple, pero no restringido

La ventaja de Portside es un gran equipo moderador. Tienen 20 voluntarios dedicados que recorren la web en busca de los mejores informes de la izquierda. La formación técnica del equipo abarca todo el espectro. Era imperativo que desarrolláramos una experiencia de creación que fuera fácil de usar para todos, sin sacrificar la funcionalidad.

Aprovechando la experiencia de creación mejorada que ofrece Drupal 8, probamos el pegado del contenido de los sitios comunes que se vuelven a publicar en Portside, asegurando que las distintas marcas de otras fuentes tuvieran reglas de CSS razonables en Portside para que los artículos se vean bien.

Incrustar Rich Media

Cuando usamos software anticuado, nos hacemos adeptos a las soluciones alternativas. Una infame para los moderadores de Portside fue la inserción de tweets. Su sistema anterior no era compatible con los códigos de inserción de Twitter. La solución fue tomar capturas de pantalla de tweets y vincular la imagen al tweet original. Utilizamos el módulo Media Entity Twitter en concierto con el módulo de Medios de Drupal Core para permitir a los editores incrustar sin problemas los tweets en sus artículos. Adiós soluciones.

Una cosa que funcionó bien en su sitio de Drupal 7 fue incrustar videos de YouTube y Vimeo. Con el módulo WYSIWYG Media Embed, simplemente necesitaban pegar la url en su artículo y se mostraría correctamente. Desafortunadamente no hubo una versión de Drupal 8 de este módulo. Así que ayudamos a portar el módulo WYSIWYG Media Embed de Drupal 7 a Drupal 8. Ahora los autores pueden incrustar fácilmente videos de YouTube y Vimeo.

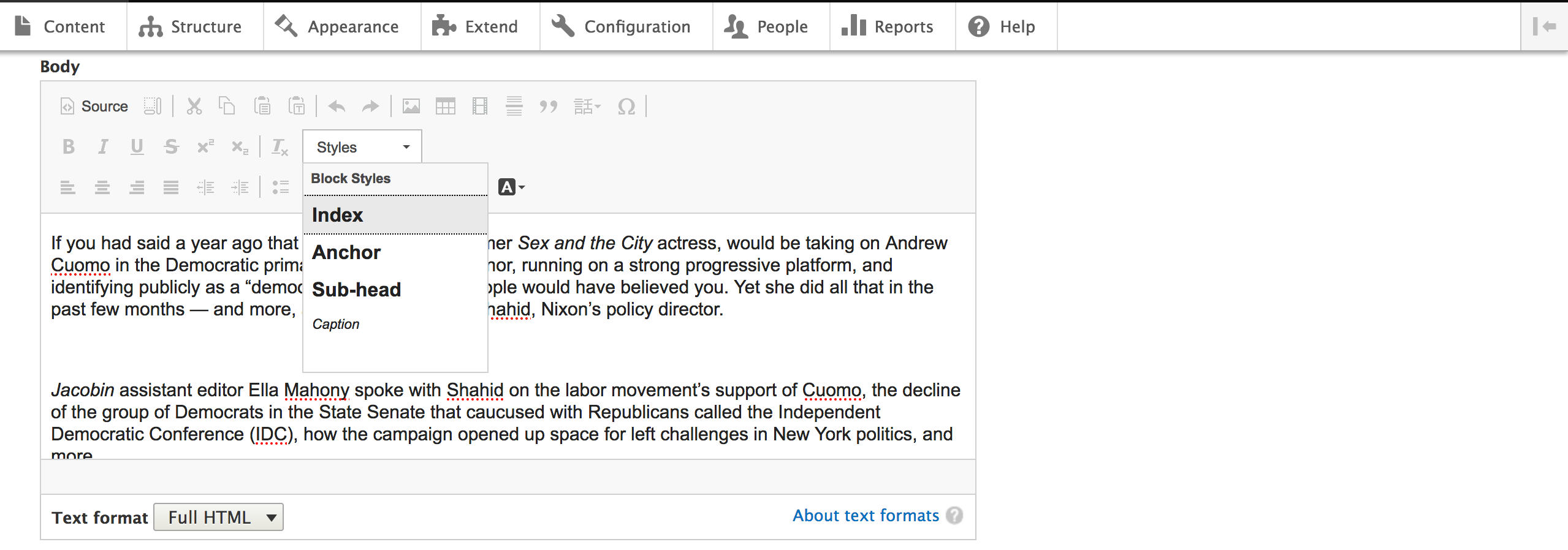

Estilos personalizados

CKEditor permite la definición de estilos personalizados que los autores pueden elegir para aplicar al texto. Esto fue útil para los autores que no están tan versados en HTML. Los autores ahora pueden aplicar estilo al texto con una terminología significativa para ellos, pero eso utiliza HTML semánticamente correcto debajo del capó.

Agregamos opciones de estilo personalizadas al editor WYSIWYG para que los moderadores puedan personalizar el contenido utilizando términos que les son familiares, pero que producen HTML y CSS compatibles con los estándares.

Agregamos opciones de estilo personalizadas al editor WYSIWYG para que los moderadores puedan personalizar el contenido utilizando términos que les son familiares, pero que producen HTML y CSS compatibles con los estándares.

Flujo de trabajo de publicación: automatizado y a prueba de errores

Para ahorrar aún más el tiempo de los editores, buscamos formas de automatizar tareas. Identificamos tres áreas: publicación de publicaciones a una hora determinada, publicación fácil en plataformas de redes sociales, publicación automatizada en servidores de listas.

Publicación Programada

Portside publica sus artículos cada día a las 8 pm hora del este. Esto les da a los autores un período de gracia para solucionar cualquier problema con su artículo antes de que se publique. Programamos esto en el sitio para que cuando un autor cree un artículo pueda guardarlo como borrador o guardarlo como artículo listo para su publicación. Cada día a las 8 p. M., Los artículos de la Hora del Este en el estado Borrador permanecen así, mientras que los Artículos en el estado Lista se publican.

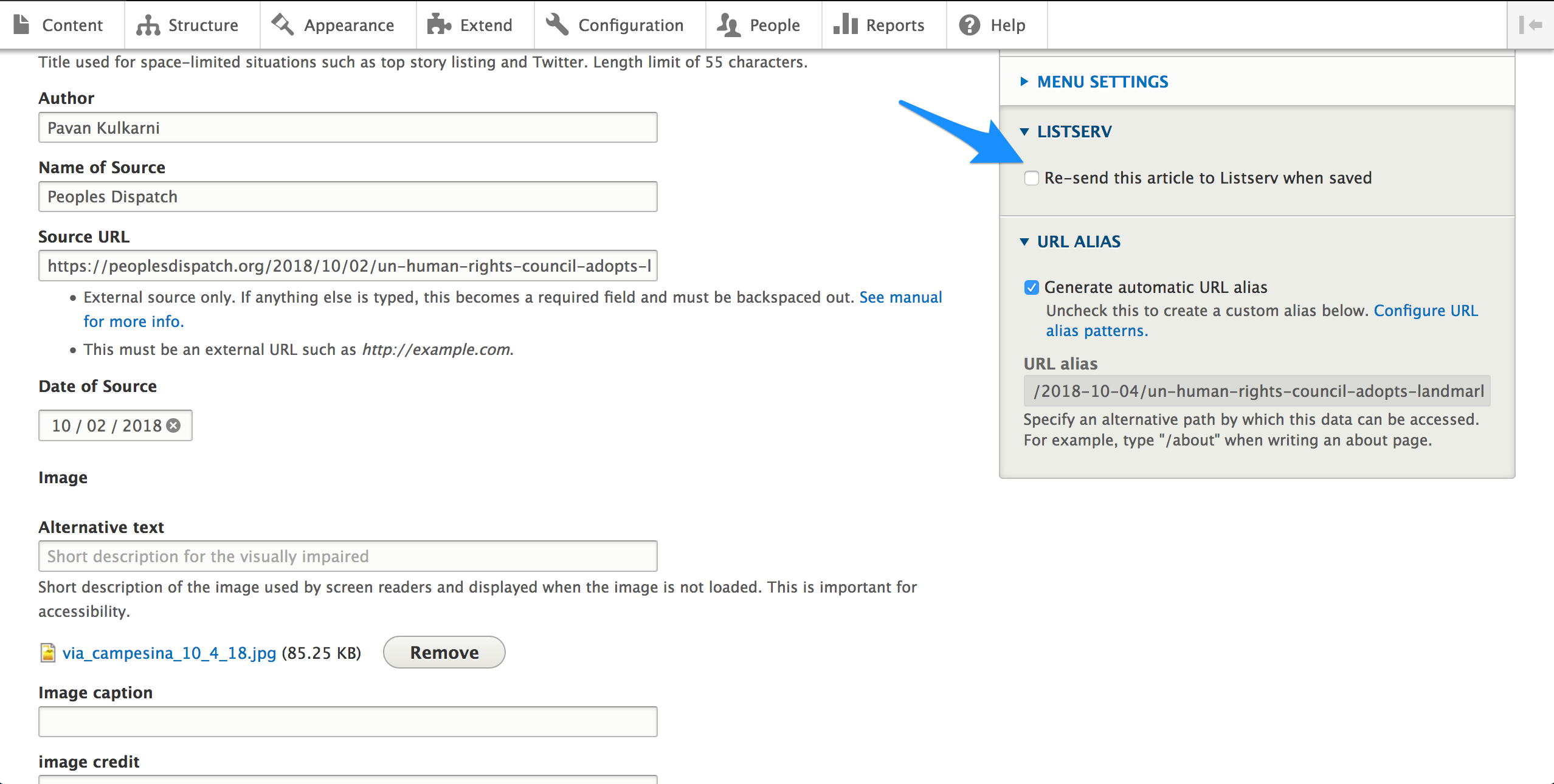

Publicación automatizada en listas

Los suscriptores de Portside pueden mantenerse actualizados con el contenido de varias maneras:

- ser enviado por correo electrónico cada nuevo artículo publicado

- ser enviado por correo electrónico artículos de una determinada categoría (General, Laboral y Cultura)

- ser enviado por correo electrónico diariamente con un resumen de los artículos publicados el día anterior (Portside Snapshot)

Construimos una integración entre el sitio web y su software listserv, Listserv, de modo que cuando se publica un artículo se envía a las listas de correo apropiadas. Para Portside Snapshot, todos los artículos publicados el día anterior se agregan en una plantilla de correo electrónico y se envían.

Con la automatización siempre existe el riesgo de error humano. Construimos en salvaguardas para los errores previsibles. Cada artículo se mantiene en una cola que espera la aprobación del moderador antes de ser enviado. Además, si un artículo se publica con un problema, un autor puede corregir el error y luego reenviar el artículo al listserv. El moderador puede descartar el primer artículo con el error y aceptar el artículo corregido de seguimiento que se enviará.

Los moderadores pueden reenviar un artículo a la cola del servidor de listas cuando hayan realizado una actualización.

Los moderadores pueden reenviar un artículo a la cola del servidor de listas cuando hayan realizado una actualización.

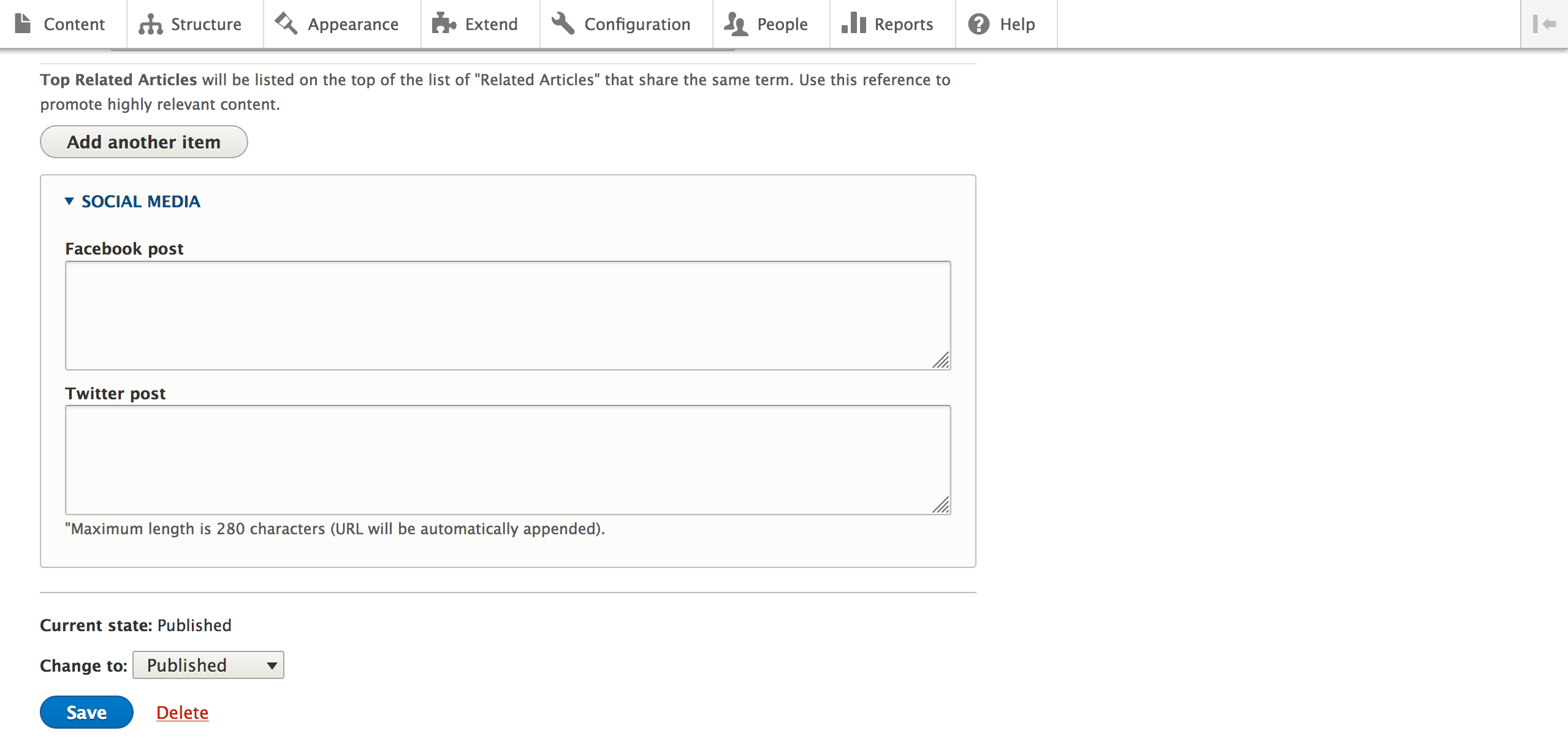

Publicar en Redes Sociales

Hemos optimizado su flujo de trabajo al equipar a los autores para que publiquen artículos en Facebook y Twitter durante el proceso de creación.

Hicimos esto contribuyendo a Drupal Social Initiative, un grupo de trabajo que armoniza la funcionalidad de las redes sociales en Drupal. Al facilitar a los autores la publicación de contenido desde su sitio web a las plataformas de redes sociales, tenemos la intención de combatir la tendencia inquietante de que cada vez haya más contenido viviendo detrás de jardines amurallados, una amenaza para la Web abierta. Los flujos de trabajo de "publicación en" sin interrupciones permiten a los autores mantener el control de su contenido y, al mismo tiempo, promocionarlo entre sus seguidores en las plataformas de redes sociales.

Social Post Facebook y Social Post Twitter agregan una página de configuración para que los usuarios vinculen su cuenta de sitio web con sus respectivas cuentas de redes sociales. El contenido publicado por un usuario se publica automáticamente en sus respectivas cuentas de redes sociales.

Para Portside, avanzamos un paso más al agregar un campo de texto en el formulario de entrada del contenido del artículo. Este campo permite a los autores ingresar el texto que desean publicar acompañando un enlace al contenido que están publicando.

Cuando los moderadores incluyen texto en los campos de redes sociales, el artículo se publica automáticamente en Facebook y / o Twitter.

Cuando los moderadores incluyen texto en los campos de redes sociales, el artículo se publica automáticamente en Facebook y / o Twitter.

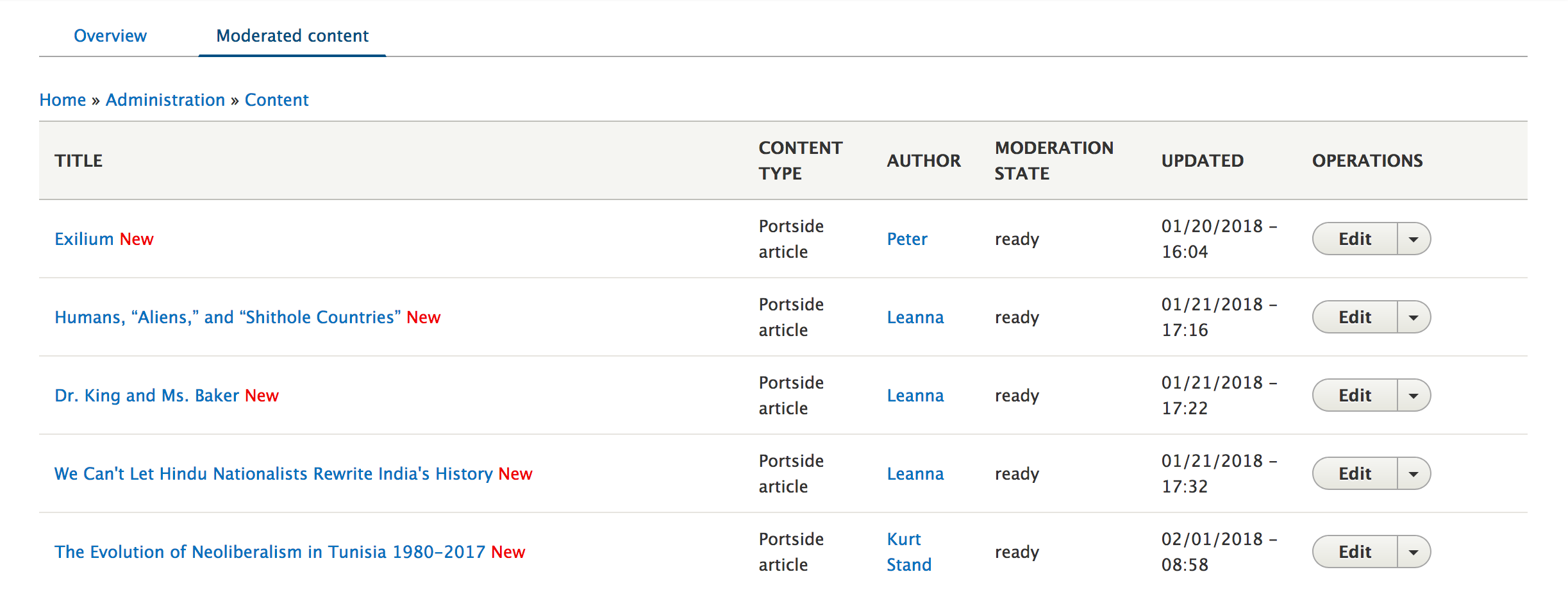

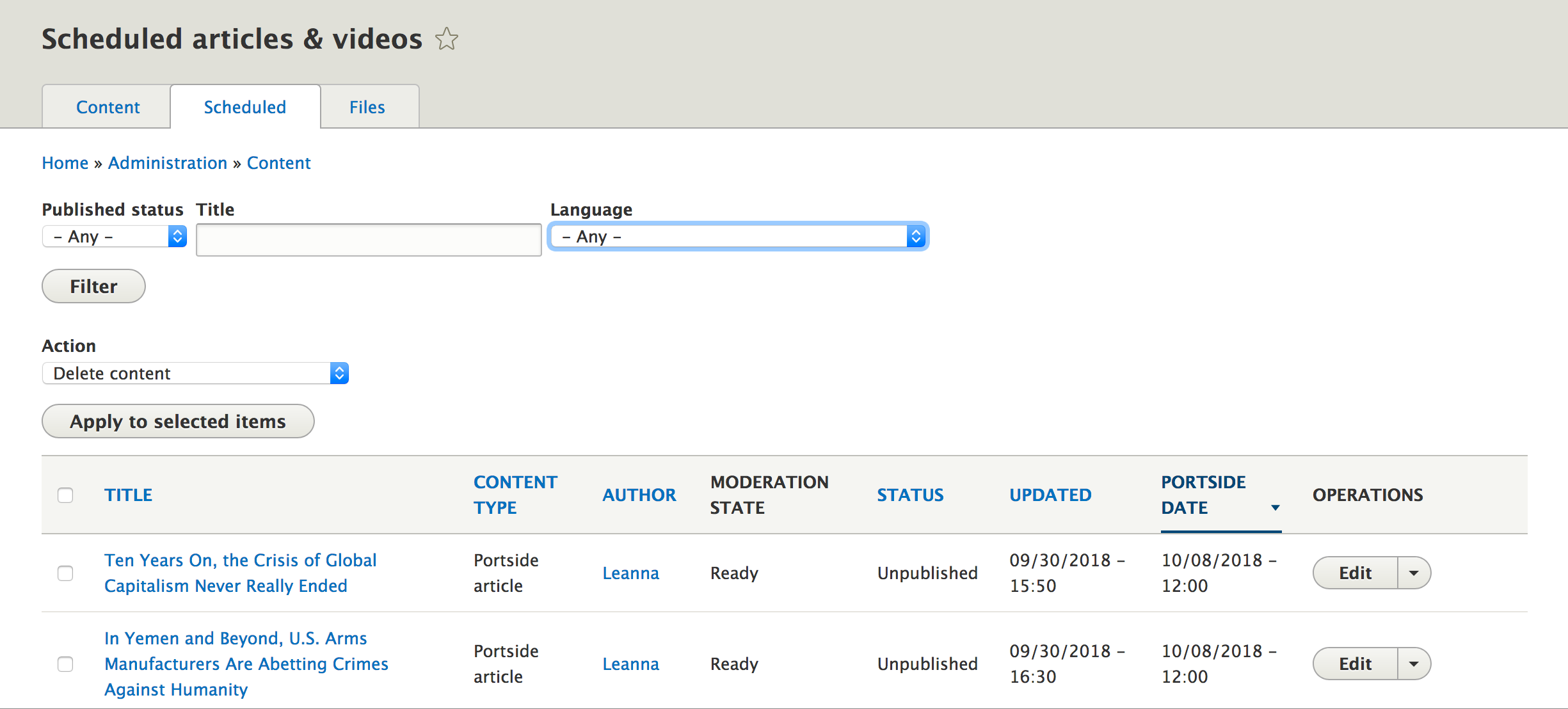

Panel de Control Significativo y Relevante del Editor

Veinte editores publican en el sitio, los visitantes del sitio sugieren que se publiquen artículos, varios artículos en borrador mientras que otros están listos pero aún no se han publicado: hay una actividad constante en portside.org; suficiente para hacer girar la cabeza. Los editores necesitaban un panel para realizar un seguimiento de todo fácilmente.

Mejoramos la página administrativa predeterminada de Drupal para que el contenido muestre el estado del flujo de trabajo personalizado del artículo y la Fecha del puerto (la fecha en que se establece que se publicará un artículo). Para ayudar a los editores a centrarse solo en los artículos que aún no se han publicado, creamos una página de Contenido moderado y, para que los artículos que están en cola para ser publicados, ahora tengan una página Programada.

Personalizamos la página de contenido administrativo predeterminado de Drupal para mostrar el estado de moderación en que se encuentra cada artículo.

Personalizamos la página de contenido administrativo predeterminado de Drupal para mostrar el estado de moderación en que se encuentra cada artículo.

Una página administrativa personalizada muestra qué artículos aún no se han publicado, pero están programados.

Una página administrativa personalizada muestra qué artículos aún no se han publicado, pero están programados.

Chris has worked in a variety of technical leadership roles for over the past two decades (and some), after first discovering his talent for programming while hacking BASIC programs at the age of 12. He returned to programming as a career - his first programming position utilizing Visual Basic - where he proved himself capable of tackling some of the most challenging obstacles.

Chris was excited to work with Agaric because: "It's a gift to be brought into a group working on building great sites, while simultaneously promoting and using solutions that benefit both our clients and our community. Agaric has clear perception of the concepts of our digital freedom, and I'm grateful to help them spread those observations through my contributions."

To learn more about the cooperative movement, visit the US Federation of Worker Owner Cooperatives.

Drupal 8 Migrations by Example (1 hour session)

Twin Cities, DrupalCon Nashville

Learn to use the Migrate API to upgrade your Drupal 6/7 site to Drupal 8/9. See how the automated upgrade procedure can help you get a head start in writing the migrations. You will have the opportunity to change your site’s information architecture as part of the upgrade process.

Drupal Core - The main functionality that all Drupal sites come with, out of the box.

Contributed Projects

We maintain more than 100 contributed modules, many of which we thought up and built:

- Advanced Help - Provide contextual help for your modules and themes.

- Bulk Invite - Bulk invite users by creating accounts with just a list of e-mail addresses.

- CKEditor Accessibility Checker - Inspect the accessibility level of your content and efficiently address issues.

- CKEditor YouTube - A video embed button for your WYSIWYG Editor.

- Comment Notify - E-mail people who comment on your site and keep them involved in discussions.

- Custom Permissions - Create custom user permissions.

- Display Role - Show users' assigned role or roles on their profile pages.

- FileField Sources - Upload files through a variety of sources.

- Gated File - Display a contact form before a visitor downloads a file.

- Give - Create and manage online donation forms within your website.

- Login Return Page - Direct users back to the page they were on when they're prompted to log into the website.

- Registration Role - Select a role to assign to new users automatically.

- Social Post Facebook - Automatically post website content to your Facebook page.

See more on our Drupal profile page.

Community Leadership

In addition to contributing to the software, we also speak at and help organize meetups, camps, and conferences. We serve as mentors and lead trainings. We also work to improve Drupal's diversity and make it an inclusive, welcoming community.

Pagination

- Previous page

- Page 14

- Next page