Portside is a digital media outlet that publishes and curates articles and videos of interest to the left. This curation lifts up critical voices in an age of media saturation and facilitates thoughtful, bold dialog online.

Cross-posted from opensource.com.

Install and configure the tools

Since it is good practice to use Composer to manage a Drupal site's dependencies, use it to install the tools for BDD tests: Behat, Mink, and the Behat Drupal Extension. The Behat Drupal Extension lists Behat and Mink among its dependencies, so you can get all of the tools by installing the Behat Drupal Extension package:

composer require drupal/drupal-extension --dev

Mink allows you to write tests in a human-readable format. For example:

Given I am registered user,

When I visit the homepage,

Then I should see a personalized news feed

Because these tests are supposed to emulate user interaction, you can assume they will be executed within a web browser. That is where Mink comes into play. There are various browser emulators, such as Goutte and Selenium, and they all behave differently and have very different APIs. Mink allows you to write a test once and execute it in different browser emulators. In layman's terms, Mink allows you to control a browser programmatically to emulate a user's action.

Now that you have the tools installed, you should have a behat command available. If you run it:

./vendor/bin/behatyou should get an error, like:

FeatureContext context class not found and can not be usedStart by initializing Behat:

./vendor/bin/behat --initThis will create two folders and one file, which we will revisit later; for now, running behat without the extra parameters should not yield an error. Instead, you should see an output similar to this:

No scenarios

No steps

0m0.00s (7.70Mb)Now you are ready to write your first test, for example, to verify that website visitors can leave a message using the site-wide contact form.

Writing test scenarios

By default, Behat will look for files in the features folder that's created when the project is initialized. The file inside that folder should have the .feature extension. Let's tests the site-wide contact form. Create a file contact-form.feature in the features folder with the following content:

Feature: Contact form

In order to send a message to the site administrators

As a visitor

I should be able to use the site-wide contact form

Scenario: A visitor can use the site-wide contact form

Given I am at "contact/feedback"

When I fill in "name" with "John Doe"

And I fill in "mail" with "john@doe.com"

And I fill in "subject" with "Hello world"

And I fill in "message" with "Lorem Ipsum"

And I press "Send message"

Then I should see the text "Your message has been sent."

Behat tests are written in Gherkin, a human-readable format that follows the Context–Action–Outcome pattern. It consists of several special keywords that, when parsed, will execute commands to emulate a user's interaction with the website.

The sentences that start with the keywords Given, When, and Then indicate the Context, Action, and Outcome, respectively. They are called Steps and they should be written from the perspective of the user performing the action. Behat will read them and execute the corresponding Step Definitions. (More on this later.)

This example instructs the browser to visit a page under the "contact/feedback" link, fill in some field values, press a button, and check whether a message is present on the page to verify that the action worked. Run the test; your output should look similar to this:

1 scenario (1 undefined)

7 steps (7 undefined)

0m0.01s (8.01Mb)

>> default suite has undefined steps. Please choose the context to generate snippets:

[0] None

[1] FeatureContext

>

Type 0 at the prompt to select the None option. This verifies that Behat found the test and tried to execute it, but it is complaining about undefined steps. These are the Step Definitions, PHP code that will execute the tasks required to fulfill the step. You can check which steps definitions are available by running:

./vendor/bin/behat -dlCurrently there are no step definitions, so you shouldn't see any output. You could write your own, but for now, you can use some provided by the Mink extension and the Behat Drupal Extension. Create a behat.yml file at the same level as the Features folder—not inside it—with the following contents:

default:

suites:

default:

contexts:

- FeatureContext

- Drupal\DrupalExtension\Context\DrupalContext

- Drupal\DrupalExtension\Context\MinkContext

- Drupal\DrupalExtension\Context\MessageContext

- Drupal\DrupalExtension\Context\DrushContext

extensions:

Behat\MinkExtension:

goutte: ~

Steps definitions are provided through Contexts. When you initialized Behat, it created a FeatureContext without any step definitions. In the example above, we are updating the configuration file to include this empty context along with others provided by the Drupal Behat Extension. Running ./vendor/bin/behat -dl again produces a list of 120+ steps you can use; here is a trimmed version of the output:

default | Given I am an anonymous user

default | When I visit :path

default | When I click :link

default | Then I (should )see the text :text

Now you can perform lots of actions. Run the tests again with ./vendor/bin/behat. The test should fail with an error similar to:

Scenario: A visitor can use the site-wide contact form # features/contact-form.feature:8

And I am at "contact/feedback" # Drupal\DrupalExtension\Context\MinkContext::assertAtPath()

When I fill in "name" with "John Doe" # Drupal\DrupalExtension\Context\MinkContext::fillField()

And I fill in "mail" with "john@doe.com" # Drupal\DrupalExtension\Context\MinkContext::fillField()

And I fill in "subject" with "Hello world" # Drupal\DrupalExtension\Context\MinkContext::fillField()

Form field with id|name|label|value|placeholder "subject" not found. (Behat\Mink\Exception\ElementNotFoundException)

And I fill in "message" with "Lorem Ipsum" # Drupal\DrupalExtension\Context\MinkContext::fillField()

And I press "Send message" # Drupal\DrupalExtension\Context\MinkContext::pressButton()

Then I should see the text "Your message has been sent." # Drupal\DrupalExtension\Context\MinkContext::assertTextVisible()

--- Failed scenarios:

features/contact-form.feature:8 1 scenario (1 failed) 7 steps (3 passed, 1 failed, 3 skipped) 0m0.10s (12.84Mb)The output shows that the first three steps—visiting the contact page and filling in the name and subject fields—worked. But the test fails when the user tries to enter the subject, then it skips the rest of the steps. These steps require you to use the name attribute of the HTML tag that renders the form field.

When I created the test, I purposely used the proper values for the name and address fields so they would pass. When in doubt, use your browser's developer tools to inspect the source code and find the proper values you should use. By doing this, I found I should use subject[0][value] for the subject and message[0][value] for the message. When I update my test to use those values and run it again, it should pass with flying colors and produce an output similar to:

1 scenario (1 passed)

7 steps (7 passed)

0m0.29s (12.88Mb)

Success! The test passes! In case you are wondering, I'm using the Goutte browser. It is a command line browser, and the driver to use it with Behat is installed as a dependency of the Behat Drupal Extension package.

Other things to note

As mentioned above, BDD tests should be written from the perspective of the user performing the action. Users don't think in terms of HTML name attributes. That is why writing tests using subject[0][value] and message[0][value] is both cryptic and not very user friendly. You can improve this by creating custom steps at features/bootstrap/FeatureContext.php, which was generated when Behat initialized.

Also, if you run the test several times, you will find that it starts failing. This is because Drupal, by default, imposes a limit of five submissions per hour. Each time you run the test, it's like a real user is performing the action. Once the limit is reached, you'll get an error on the Drupal interface. The test fails because the expected success message is missing.

This illustrates the importance of debugging your tests. There are some steps that can help with this, like Then print last drush output and Then I break. Better yet is using a real debugger, like Xdebug. You can also install other packages that provide more step definitions specifically for debugging purposes, like Behatch and Nuvole's extension,. For example, you can configure Behat to take a screenshot of the state of the browser when a test fails (if this capability is provided by the driver you're using).

Regarding drivers and browser emulators, Goutte doesn't support JavaScript. If a feature depends on JavaScript, you can test it by using the Selenium2Driver in combination with Geckodriver and Firefox. Every driver and browser has different features and capabilities. For example, the Goutte driver provides access to the response's HTTP status code, but the Selenium2Driver doesn't. (You can read more about drivers in Mink and Behat.) For Behat to pickup a javascript enabled driver/browser you need to annotate the scenario using the @javascript tag. Example:

Feature:

(feature description)

@javascript

Scenario: An editor can select the author of a node from an autocomplete field

(list of steps)

Another tag that is useful for Drupal sites is @api. This instructs the Behat Drupal Extension to use a driver that can perform operations specific to Drupal; for example, creating users and nodes for your tests. Although you could follow the registration process to create a user and assign roles, it is easier to simply use a step like Given I am logged in as a user with the "Authenticated user" role. For this to work, you need to specify whether you want to use the Drupal or Drush driver. Make sure to update your behat.yml file accordingly. For example, to use the Drupal driver:

default:

extensions:

Drupal\DrupalExtension:

blackbox: ~

api_driver: drupal

drupal:

drupal_root: ./relative/path/to/drupal

I hope this introduction to BDD testing in Drupal serves you well. If you have questions, feel free to add a comment below, send me an email at mauricio@agaric.com (or through the Agaric contact form) or a tweet at @dinarcon.

The .org domain conveys a nonprofit status to most of us, differentiated from the for-profit connotations of .com (or the emphatically for-profit .biz). However, the nonprofit nature of the TLD was lost as of November 13th. The private equity firm Ethos Capital bought Public Interest Registry, the nonprofit that managed .org. In other words, a nonprofit TLD is now run by a for-profit investment firm.

The adherence to nonprofit values was already loose with .org. A group didn't have to prove in any way it was a nonprofit or community organization. Still, it was run by a nonprofit that describes themselves this way-

"Acting in the public interest. As our name implies, PIR serves the public interest online. Our globally diverse team is committed to providing a stable online platform to enable people to do good things."

Internet Society, the nonprofit that created PIR, defends the sale by basically stating that the money they're getting will help them do their work better.

However, private acquisition of nonprofit entities inherently changes the structure and ultimate goals of a group. It's almost certain this means an eventual increase in prices for .org domains - a logical move for a firm that needs to increase its profit margins. What else could this mean for the .org community? Perhaps the already loose definition of who .org is intended for will be relaxed further to expand the market.

A better model would be a platform cooperative, in which the purchasers of .org domains become members of the cooperative. A cooperative is bound to its stakeholders, ensuring on a structural level that the .org domain really is managed to provide "a stable online platform to enable people to do good things."

Whatever the real world implications of this move, one thing is clear- in a time when the internet as a public good needs to be treated, owned and governed as such, this privatization of our movement's tools is a disturbing event in a larger troubling trend.

Where do we go from here?

Shortening Sequential Lists

In Other Words can also shorten sequential lists by skipping over the items in the middle of the sequence. For example, if the following full list is available:

Sunday, Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday

And a content author selects the following from them:

Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday

The In other words: Sequential terms formatter can be configured to interpret this and output:

Monday through Thursday.

It even accounts for breaks between sequential items. For example:

Monday through Thursday and Saturday.

And if you want to get real fancy, you can group terms together under a single label, such as interpreting Saturdays and Sundays as "the weekend".

Finally, you can have In Other Words output a single phrase if all items are selected. For example, "All Days".

Do so by using the In Other Words: Sequential terms field formatter, which supports term reference fields.

Drupal upgrades

Migrating content to your new site

Starting at $1,250 for five hours a month, Agaric will maintain your current site with all security updates, provide support, make continuous improvements, and be available for our full range of consulting capabilities.

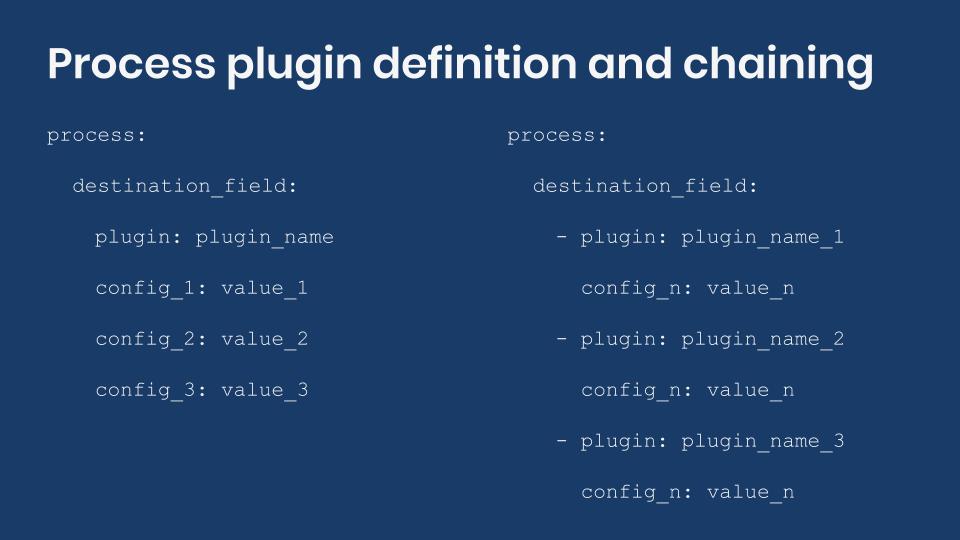

In the previous entry, we wrote our first Drupal migration. In that example, we copied verbatim values from the source to the destination. More often than not, the data needs to be transformed in some way or another to match the format expected by the destination or to meet business requirements. Today we will learn more about process plugins and how they work as part of the Drupal migration pipeline.

Syntactic sugar

The Migrate API offers a lot of syntactic sugar to make it easier to write migration definition files. Field mappings in the process section are an example of this. Each of them requires a process plugin to be defined. If none is manually set, then the get plugin is assumed. The following two code snippets are equivalent in functionality.

process:

title: creative_title

process:

title:

plugin: get

source: creative_title

The get process plugin simply copies a value from the source to the destination without making any changes. Because this is a common operation, get is considered the default. There are many process plugins provided by Drupal core and contributed modules. Their configuration can be generalized as follows:

process:

destination_field:

plugin: plugin_name

config_1: value_1

config_2: value_2

config_3: value_3

The process plugin is configured within an extra level of indentation under the destination field. The plugin key is required and determines which plugin to use. Then, a list of configuration options follows. Refer to the documentation of each plugin to know what options are available. Some configuration options will be required while others will be optional. For example, the concat plugin requires a source, but the delimiter is optional. An example of its use appears later in this entry.

Providing default values

Sometimes, the destination requires a property or field to be set, but that information is not present in the source. Imagine you are migrating nodes. As we have mentioned, it is recommended to write one migration file per content type. If you know in advance that for a particular migration you will always create nodes of type Basic page, then it would be redundant to have a column in the source with the same value for every row. The data might not be needed. Or it might not exist. In any case, the default_value plugin can be used to provide a value when the data is not available in the source.

source: ...

process:

type:

plugin: default_value

default_value: page

destination:

plugin: 'entity:node'

The above example sets the type property for all nodes in this migration to page, which is the machine name of the Basic page content type. Do not confuse the name of the plugin with the name of its configuration property as they happen to be the same: default_value. Also note that because a (content) type is manually set in the process section, the default_bundle key in the destination section is no longer required. You can see the latter being used in the example of writing your Drupal migration blog post.

Concatenating values

Consider the following migration request: you have a source listing people with first and last name in separate columns. Both are capitalized. The two values need to be put together (concatenated) and used as the title of nodes of type Basic page. The character casing needs to be changed so that only the first letter of each word is capitalized. If there is a need to display them in all caps, CSS can be used for presentation. For example: FELIX DELATTRE would be transformed to Felix Delattre.

Tip: Question business requirements when they might produce undesired results. For instance, if you were to implement this feature as requested DAMIEN MCKENNA would be transformed to Damien Mckenna. That is not the correct capitalization for the last name McKenna. If automatic transformation is not possible or feasible for all variations of the source data, take notes and perform manual updates after the initial migration. Evaluate as many use cases as possible and bring them to the client’s attention.

To implement this feature, let’s create a new module ud_migrations_process_intro, create a migrations folder, and write a migration definition file called udm_process_intro.yml inside it. Follow the instructions in this entry to find the proper location and folder structure or download the sample module from https://github.com/dinarcon/ud_migrations It is the one named UD Process Plugins Introduction and machine name udm_process_intro. For this example, we assume a Drupal installation using the standard installation profile which comes with the Basic Page content type. Let’s see how to handle the concatenation of first an last name.

id: udm_process_intro

label: 'UD Process Plugins Introduction'

source:

plugin: embedded_data

data_rows:

-

unique_id: 1

first_name: 'FELIX'

last_name: 'DELATTRE'

-

unique_id: 2

first_name: 'BENJAMIN'

last_name: 'MELANÇON'

-

unique_id: 3

first_name: 'STEFAN'

last_name: 'FREUDENBERG'

ids:

unique_id:

type: integer

process:

type:

plugin: default_value

default_value: page

title:

plugin: concat

source:

- first_name

- last_name

delimiter: ' '

destination:

plugin: 'entity:node'

The concat plugin can be used to glue together an arbitrary number of strings. Its source property contains an array of all the values that you want put together. The delimiter is an optional parameter that defines a string to add between the elements as they are concatenated. If not set, there will be no separation between the elements in the concatenated result. This plugin has an important limitation. You cannot use strings literals as part of what you want to concatenate. For example, joining the string Hello with the value of the first_name column. All the values to concatenate need to be columns in the source or fields already available in the process pipeline. We will talk about the latter in a future blog post.

To execute the above migration, you need to enable the ud_migrations_process_intro module. Assuming you have Migrate Run installed, open a terminal, switch directories to your Drupal docroot, and execute the following command: drush migrate:import udm_process_intro Refer to this entry if the migration fails. If it works, you will see three basic pages whose title contains the names of some of my Drupal mentors. #DrupalThanks

Chaining process plugins

Good progress so far, but the feature has not been fully implemented. You still need to change the capitalization so that only the first letter of each word in the resulting title is uppercase. Thankfully, the Migrate API allows chaining of process plugins. This works similarly to unix pipelines in that the output of one process plugin becomes the input of the next one in the chain. When the last plugin in the chain completes its transformation, the return value is assigned to the destination field. Let’s see this in action:

id: udm_process_intro

label: 'UD Process Plugins Introduction'

source: ...

process:

type: ...

title:

-

plugin: concat

source:

- first_name

- last_name

delimiter: ' '

-

plugin: callback

callable: mb_strtolower

-

plugin: callback

callable: ucwords

destination: ...

The callback process plugin pass a value to a PHP function and returns its result. The function to call is specified in the callable configuration option. Note that this plugin expects a source option containing a column from the source or value of the process pipeline. That value is sent as the first argument to the function. Because we are using the callback plugin as part of a chain, the source is assumed to be the last output of the previous plugin. Hence, there is no need to define a source. So, we concatenate the columns, make them all lowercase, and then capitalize each word.

Relying on direct PHP function calls should be a last resort. Better alternatives include writing your own process plugins which encapsulates your business logic separate of the migration definition. The callback plugin comes with its own limitation. For example, you cannot pass extra parameters to the callable function. It will receive the specified value as its first argument and nothing else. In the above example, we could combine the calls to mb_strtolower() and ucwords() into a single call to mb_convert_case($source, MB_CASE_TITLE) if passing extra parameters were allowed.

Tip: You should have a good understanding of your source and destination formats. In this example, one of the values to want to transform is MELANÇON. Because of the cedilla (ç) using strtolower() is not adequate in this case since it would leave that character uppercase (melanÇon). Multibyte string functions (mb_*) are required for proper transformation. ucwords() is not one of them and would present similar issues if the first letter of the words are special characters. Attention should be given to the character encoding of the tables in your destination database.

Technical note: mb_strtolower is a function provided by the mbstring PHP extension. It does not come enabled by default or you might not have it installed altogether. In those cases, the function would not be available when Drupal tries to call it. The following error is produced when trying to call a function that is not available: The "callable" must be a valid function or method. For Drupal and this particular function that error would never be triggered, even if the extension is missing. That is because Drupal core depends on some Symfony packages which in turn depend on the symfony/polyfill-mbstring package. The latter provides a polyfill) for mb_* functions that has been leveraged since version 8.6.x of Drupal.

What did you learn in today’s blog post? Did you know that syntactic sugar allows you to write shorter plugin definitions? Were you aware of process plugin chaining to perform multiple transformations over the same data? Had you considered character encoding on the source and destination when planning your migrations? Are you making your best effort to avoid the callback process plugin? Please share your answers in the comments. Also, I would be grateful if you shared this blog post with your colleagues.

Next: Migrating data into Drupal subfields

This blog post series, cross-posted at UnderstandDrupal.com as well as here on Agaric.coop, is made possible thanks to these generous sponsors. Contact Understand Drupal if your organization would like to support this documentation project, whether is the migration series or other topics.

Create a user account

Set event reminders about interesting opportunities and receive notifications.

Interested in Public Trainings?

Overview

You've built a Drupal site or three and know that with a few dozen modules (and a ton of configuring), you can do nearly everything in modern Drupal. But what do you do when there's not a module for that?

You make your own!

This training will guide you through taking that step, and the crucial next step of maintaining your new module.

Building and contributing a module so that it is available officially on Drupal.org is a huge way to both deepen your connection to Drupal and further unlock Drupal's power to help you and your organization.

In this full-day training, the first three hours will cover creating a brand new module.

The second half of the day, after lunch, will cover how to make your new module contrib-worthy and how to maintain that module for, and in collaboration with, the Drupal community.

This training builds on the popular DrupalCamp session of the same name, going beyond an introduction and quick tips to dive much deeper into making and maintaining Drupal modules.

Request a Private Training

Industry audit and competitive review

You may in many ways be without peer, but there are always competitors for the attention of your audience. Identifying top peers and reviewing their respective content helps you get a wider perspective both on what potential listeners, members, and donors will be seeing and what seems to be working for others— we can start thinking together about where to emulate and where to differentiate, informing all of our work together.

Content strategy

Building on the review of peers, Agaric will work with you to briefly interview current and potential clients and develop personas and user stories.

Content style guide

Along with bringing consistency to cooperative output (and saving time sweating the details every time they come up), a good content (copywriting) style guide incorporates suggestions for clear and effective writing and helps your unique aspects shine through. It can help tell your story in a consistent way and help let your individual personalities show through while maintaining collective coherence.

User research and testing

Agaric applies a Lean UX Research methodology to answer critical user experience questions with relevant, meaningful, and actionable data.

From reviewing your goals and audiences we recommend answering the following questions:

- What prevents users from becoming paying subscribers or sustaining donor members on the site?

- What features would enable users to invite friends to become supporters?

- Who is most engaged? least engaged?

- Which conversion goals are being met? unmet?

- What new audience do we want to reach?

We recommend and use the following research and testing approaches:

- A/B testing

- Brand audit

- Browser and device analysis

- Competitive analysis

- Content audit

- Contextual inquiry

- Heat map analysis

- Heuristic evaluation

- Site analytics review

- SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) analysis

- Usability testing

- User interviews

- User surveys

Not all will fit the purpose or budget of every part of a project, but good insights into what to build and why is more valuable than simply building well and quickly.

User testing & revisions

We always recommend at least one round dedicated to measuring and improving. Using analytics and user tests, we identify what is working, what is not and needs to be changed, and what is missing and needs to be built. We then build on the previous work to do the fixes and enhancements with the highest expected impact.

A program is free software if the program's users have the four essential freedoms:

- The freedom to run the program as you wish, for any purpose (freedom 0).

- The freedom to study how the program works, and change it, so it does your computing as you wish (freedom 1).

- The freedom to redistribute copies so you can help others (freedom 2).

- The freedom to distribute copies of your modified versions to others (freedom 3).

Access to the source code is a precondition for this. To determine whether the source code is free, see what license it carries and then check the GNU project's list of licenses.

We do a few tasks that we do not have free software for. So, we use non-free programs for them. Sometimes we use specific non-free software that a client insists on including in the web site. By using non-free programs, we sacrifice some of our freedom; some activists would refuse to do that. We do not like the compromise, so we help develop free replacements for those programs. Whenever possible, we use software that reflects our values.

Operating Systems

GNU/Linux

We have chosen to use GNU/Linux as our default system for our local development. When we take on a new student, we install a GNU/Linux distribution. We always give the option of installing a different distribution, or if a student wishes to do so, they may. These are the favored GNU/Linux distributions in use by our cooperative team *members:

These are not the best versions of GNU/Linux in regards to being completely free; you should consult the list of free distributions on the Free Software Foundation website.

* Currently one team member is using the proprietary but BSD-based Mac OS X, which is compliant with the Unix 03 / POSIX standard which GNU/Linux distributions also meet.

Browsers

Firefox

As developers, we have to test client sites in all browsers, but for working and building sites, we use Mozilla Firefox. Although the source code of Firefox is free software, they include some icons, trademarks, and logos in the download that make it non-free. You can easily remove these as has been done with IceCat, the GNU version of the Firefox browser. It has great performance, developer tools, and community. The plus side of having a community around the software we use is having access to a large pool of people with experience and guidance as we learn and build together.

Tor Browser

As citizens, we are not fond of being tracked, so we use a free anonymizing web browser that does not allow tracking. It is called Tor.

Micky uses and loves the Brave browser on Android and her GNU/Linux laptop. It blocks ADs right out of the box! https://brave.com/

Without looking deeply at Qwant, it looks pretty decent - https://www.qwant.com/

We came across Qwant via https://iridiumbrowser.de/ - a more secure chromium release, but probably has some things we may not know about or want...

File Storage and Calendar

NextCloud

NextCloud is a collection of utilities suited for the De-Googlization process. It provides most of the popular tools in Google Drive. Agaric uses a hosted version of NextCloud on MayFirst.org servers that is inclusive of:

- document and file storage

- shared document editing

- multi-device synchronization

- image galleries

- calendar

- contacts

See a comparison of the features NextCloud offers vs. the proprietary options like GoogleDocs/Drive.

Finance, Accounting, and Bookkeeping

GNUcash

Accounting software that we use for our bookkeeping.

You can see a review of GNUcash vs. Quickbooks and decide if it works for you. We have found a few bookkeeping cooperatives that do accounting with GnuCash.

Real-time Chat

As a team, we rely on different tools to communicate with each other and with clients about daily activities and long term project goals. We have a distributed team at locations around the world and must maintain contact especially when pair-programming or during a migration which calls for all-hands-on-deck, as well as sharing some long informational text notes and documents that include administrative information.

Freenode

IRC - Internet Relay Chat - Realtime Text Chat: Yes, we still use IRC, and you can find us on irc.freenode.net server in the #devs-r-us channel

Our preferences here are as varied as our team members: some use irssi via a remote, always-on virtual server, many use desktop clients, such as HexChat or Konversation, and still, others prefer the web-based solution "The Lounge."

MayFirst.org hosts Agaric.com email

Email Client: Thunderbird

An email client from Mozilla, which also makes Firefox, and is available for your phone. It also has an encryption plugin called EnigMail that works well and is not super tricky to get set up.

Hosted Email: RiseUp: Encrypted services run by anonymous volunteers and you must be invited to have a membership.

MayFirst offers three web-based email solutions.

- Roundcube which has a friendly and simple web interface, making it the easier of the two programs to use.

- SquirrelMail is an option that is Javascript-free!

- Horde, on the other hand, offers more than just email - you can share calendars, to-dos and more with other members of your group.

Hosted Email

Protonmail: An email service that is hosted and encrypted.

Email Lists:

We use email list servers for mailing lists based on groups and topics. It allows group mailing to people that sign up for a specific list.

MayFirst Email Server

RiseUp Email Server

Social Media

Mastodon: Publish anything you want: links, pictures, text, video. All on a platform that is community-owned and ad-free.

Social.coop: A community similar to Twitter, the main difference is that it is owned by the members. For as little as $1 a month you can become an owner/member and take part in shaping the future of the platform. You can find and follow Agaric in social.coop, a coop-run corner of the fediverse, a cooperative and transparent approach to operating a social platform

Live Streaming

MayFirst Live Streaming: MayFirst membership includes live streaming.

Conference Calls and Online Meetings

Some Agaric team members are using Jitsi recognizing that it is a work in progress and there may be technical failures at times - such as we have also found using Google Hangouts - lag time, cut-offs, poor sound quality and issues with screen sharing. At times we have found that we need to use a proprietary solution that seems to work reliably as we continue to support development efforts and bug fixes with Jitsi. At the heart of Jitsi are Jitsi Videobridge and Jitsi Meet, which let you have conferences on the internet, while other projects in the community enable other features such as audio, dial-in, recording, and simulcasting.

You can self-host an instance of Jitsi or choose a hosted version. You can use http://meet.jit.si or an instance is also available for public use at https://meet.mayfirst.org We do encourage you to become a MayFirst member and have access to all of the free software tools they offer. The Jitsi project needs volunteers to use and test Jitsi so it can get better swiftly!

Currently, Agaric was using and paying for, the proprietary Zoom audio/video conference call service and software. Since October we have been using BigBlueButton a free software alternative. BBB has been working well for us and we have worked it into being our go-to solution for protecting our privacy.

BigBlueButton

BigBlueButton.org: Agaric uses BigBlueButton as our video-chat meeting platform. We also offer free chatroom hosting for those that cannot afford to pay for this service.

Phone Calls and Text Messages

Signal: Agaric uses Signal to encrypt SMS text messages and phone calls. Encrypted phone and instant messaging found to be secure and recommended by Edward Snowden as the only truly encrypted messaging app that is not able to be decrypted by anyone. Note that security is an arms race and this could become false at any time.

Collaborative Note Taking

Etherpad: When hosting an online meeting we usually open a shared note pad so that everyone may contribute to getting the important bits logged. Etherpad text is synchronized as you type so that everyone viewing the page sees the same text. This allows you to collaborate on documents with large or small teams seamlessly! We use the hosted version, but you are welcome to host it yourself. We have tried a few online pads and settled on Etherpad as the most reliable.

Collaborative Ongoing Discussion

With some collaborators, particularly people involved with the Drutopia initiative, we use Mattermost rather than IRC. Mattermost can be more useful for ongoing discussions; it is similar to Slack and offers a threaded conversation. The community version is free software.

Notes and ToDo Lists

TomBoy A tiny app that lets you take notes while it conveniently makes hyperlinks out of titles and allows synchronization over SSH and more.

Password Management

KeePass A password management system that takes most of the worry, distraction and thinking out of storing and retrieving your login information for multiple projects and sites.

Text Document Editing, Spreadsheets, and Presentations

Libre Office: A suite of office tools similar to Microsoft Office, Documents, Spreadsheets, Slides. We use LibreOffice tools that come as core software in the distributions of GNU/Linux we are using. You may have heard of OpenOffice; it is now called LibreOffice. It consists of basic publishing and calculating software for doing office tasks. These are the ones we use most often:

1. LibreOffice Calc - Similar features and functions of a calculating software to make spreadsheets, such as MicroSoft Excel

2. LibreOffice Writer - Similar features and functions of a word processor such as MicroSoft Word

3. LibreOffice Impress - We use this tool to build slide decks and presentations using text/graphics and videos; it is similar to Microsoft PowerPoint in features.

Project Management and Issue Tracking

*GitLab: This tool is a web-based and self-hosted Git-repository manager with a wiki and issue-tracking features. We also use Gitlab for cooperative development on our projects.

*Although GitLab isn't fully free software, it does offer a self-hosted version that is. The Enterprise hosted version has extra features and is proprietary.

Redmine: A free program that you can run locally or on your own server for use as a project management and issue tracking tool. Before finding GitLab, we used a self-hosted instance of Redmine which is free software.

Decision Making and Voting

Loomio: A hosted service available at http://loomio.org

Loomio offers distributed decision-making system where you can make groups that can have discussions and make decisions without an in-person meeting. Decide yes or no, or that you need more information.

Note that Loomio also has built a great cooperative resource on at their other URL - http://loomio.coop

Customer Relationship Management

CiviCRM: Agaric is working with the developers at MyDropWizard to take a look at CiviCRM with Drupal 8.

CiviCRM is a free software to manage client relationships and memberships. We have not deployed it yet.

Resources and Free Software Directories

- Free Software Directory

- Awesome-list of self-hosted applications

- You can search for Free software alternatives. - be sure to search for Free/Open Source, not the free trial software, and LOOK at the license.

You can contribute to groups working towards solutions, there are many roles, and you do not have to be a developer. As an example, *IndieWeb and Jitsi are projects that we make time to support with development, testing, outreach, and feedback.

*With IndieWeb, you can take control of your articles and status messages can go to all services, not just one, allowing you to engage with everyone. Even replies and likes on other services can come back to your site, so they’re all in one place.

Framasoft: A large collection of free software tools where we use the calendar and polling software most often. We are experimenting with several other FramaSoft tools and may adopt them in the future.

If this has been a helpful read, please pass it on and let us know in the comments how it helped you. A follow-up post will list the tools we use for development purposes. Please be sure to mention any free software you have found and are using now.

I will leave you with an excellent TEDx talk where Richard Stallman explains Free Software:

Pagination

- Previous page

- Page 15